Sensor opportunities: LVIT technology offers more flexibility for less money in factory automation applications

May 24, 2016

By Edward E. Herceg Alliance Sensors Group

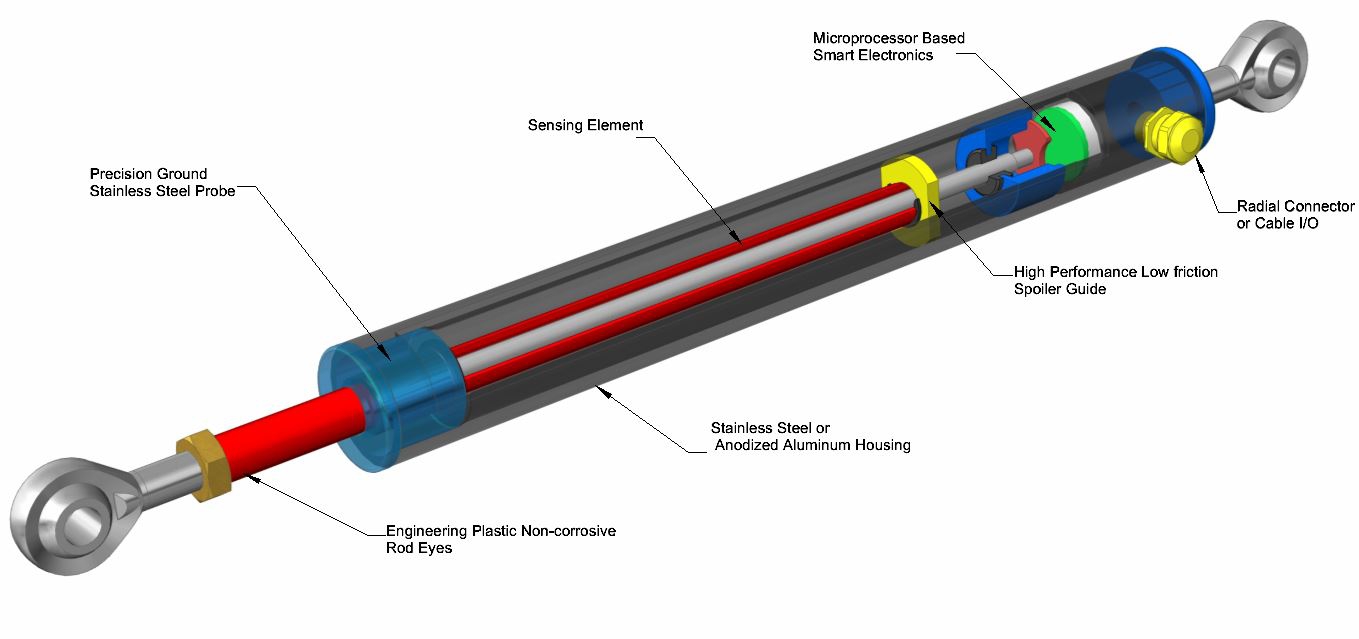

Jan. 15, 2016 – What is an LVIT and where is it used? LVITs — Linear Variable Inductive Transducers — which have been around for more than 30 years, are relatively low cost, contactless position sensing devices that utilize eddy currents developed by an inductor in the surface of a conductive movable element that is mechanically coupled to the moving object whose position is being measured. The common form of an LVIT uses a small diameter inductive probe surrounded by a conductive tube called a spoiler. Typical LVITs have full ranges from fractions of an inch to 30 or more inches. Modern electronics utilizing microprocessors make possible outstanding performance, achieving linearity errors of less than ±0.15 per cent of FSO and temperature coefficients of 50 ppm/oF, along with either analogue or digital outputs.

LVITs are used in many factory automation applications, including packaging and material handling equipment, die platen position in plastic molding machines, roller positioning and web tension controls in paper mills or converting facilities, and robotic spray painting systems. Being contactless, the basic measurement mechanism of an LVIT does not wear out over time due to rapid cycling or dithering like a resistive device. LVITs also offer a much lower installed cost than that of most other contactless technologies.

While Figure 1 shows an LVIT that is intended to be attached to the part it is measuring, LVITs can also be spring-loaded, as shown in Figure 2. The natural question is: where does one use a spring-loaded LVIT sensor versus another spring-loaded technology, such as an LVDT (Linear Variable Differential Transformer) gage head?

In fact, LVITs can be used in place of traditional gage heads primarily because, electrically, an LVIT offers the same resolution and repeatability, and mechanically, the same outer diameter and an external mounting thread but with about half of the length of the gage head —making the stroke-to-length ratio of an LVIT substantially better. And all of these features come at a markedly lower cost. Why utilize a 9-in. long sensor to measure 1 in. of travel when the same performance can be achieved with a 4-in. long LVIT sensor? LVIT-based gaging applications in factory automation typically mirror those for traditional gage heads, as shown here.

When compared to LVDT pencil gaging probes, a spring-loaded LVIT can satisfy many of the same applications: automotive, medical and mil/aero test stands, robotic arms, part placement, and shop floor dimensional gaging applications, to name a few. Pencil probes are typically selected for one of two reasons: resolution and repeatability, or size. Pencil probes are smaller (either 8 mm or 0.375-in. OD) than LVITs and have resolution and repeatability of four millionths of an inch. However a pencil probe requires a separate LVDT signal conditioner, making the cost per channel typically double the cost of an LVIT. If an application does not require the specific features of a pencil probe, a spring-loaded LVIT is a much lower cost alternative.

Some factory automation applications that have been solved by proximity sensors can be better satisfied with LVIT technology, which offers a proportional analogue output, giving greater control flexibility than merely an NPN or PNP TTL switching signal. The spring-loaded LVIT shown in Figure 2 has an 18-mm thread on its housing, matching a thread commonly used by proximity sensor manufacturers. With an LVIT’s short body length, the sensor can fit in places or mountings where there previously was a proximity probe.

Edward E. Herceg is currently vice president and chief technology officer of Alliance Sensors Group, a division of H. G. Schaevitz LLC. With a career in the sensors industry spanning more than half a century, he is highly regarded both for his applications engineering expertise and for his technical innovations.

This feature was originally published in the November/December 2015 issue of Manufacturing AUTOMATION.

Advertisement

- No interruptions here: The power of keeping manufacturing productive

- The perils of upgrading interlocking switches