Managing hazards in a hazardous world

February 18, 2019

By Garrett Potter

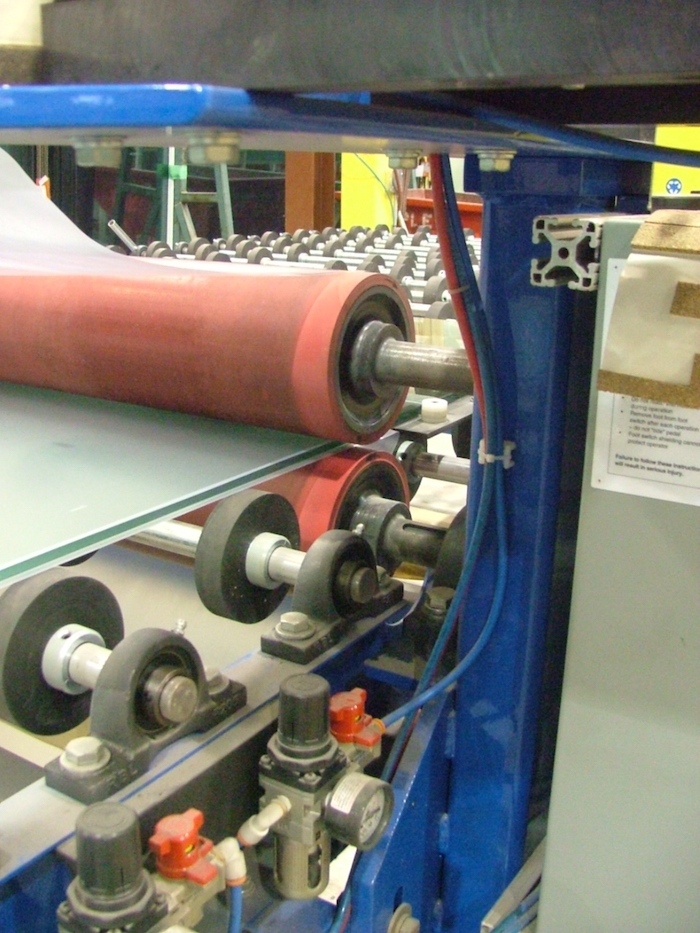

This image shows machinery with no guarding. Employers must take every reasonable precaution to protect workers.

This image shows machinery with no guarding. Employers must take every reasonable precaution to protect workers. February 18, 2019 – Modern machine safety practices call for the use of guarding, personal protective equipment and proper training, but ensuring the appropriate levels of machine safety can be a complicated task.

I sat down with Jim Farmer, P.Eng, of Industrial Performance Group, and Mike Flood, P. Eng. and engineering manager at Tenneco in Owen Sound, to discuss the importance of identifying and managing hazards in the workplace.

Farmer goes into every engineering challenge with the mindset of, “Where will an accident happen from the risks that I am seeing?” Farmer has been a professional engineer for 34 years, 23 of which he has been self-employed. He cultivated his interest in engineering and machine safety at his family machine shop as a young boy, and is now a consulting machine safety specialist who does anywhere from 50 to 100 projects a year. Most projects, whether one machine or a whole plant, involve a risk assessment. Farmer documents risks on a one-page-per-issue format, with a photo of the hazard, a description of the risk, an excerpt of the regulation or standard involved and a recommendation.

In current regulation, the machine manufacturer is not responsible for safety, while the employer must take “every precaution reasonable in the circumstances for the protection of the worker.” Things were not always this way though – when Farmer started, he found that the safety was more or less left up to the employee, not the employer.

Farmer believes that employees should be expected to give an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay. Being injured on the job should not be part of the exchange. Farmer must use everything he has learned to stay on top of the different mechanical, electrical and human factors that make machine safety such a unique puzzle. For example, the law states that you must prevent access to hazards to protect the worker. “We used to wonder why an employee would stick their hand in there; now we have to determine how,” he says.

Farmer provides a simple numbers example of just why machine safety is so important. Assuming a manufacturing process takes six seconds, in an eight-hour period (with lunch and breaks), employees can perform a process as many as 4,200 times. Even if the employee was 99 percent accurate, that is still 42 times a shift that a worker can get out of sync and put their hand in the wrong place before they hit the start button again. The inherent inaccuracy of humans is the reason that the machine itself must protect the safety of the worker.

From here, our conversation turned mostly to risk management systems verses striving for compliance. Mike Flood pointed out that compliance with regulations is of course a legal requirement, but it is not the best place to start when managing hazards. To best manage hazards, engineers like Flood and Farmer look at all of the possible injuries that could arise, and work backwards from there.

Flood also pointed out that large multinational companies like Tenneco share certain machines around the world where jurisdictional requirements for health and safety can vary, so their machines are designed to consider and mitigate every possible hazard, which often far exceed the local legal requirements.

I asked why someone would want to circumvent machine safety guidelines, to which they could think of four main reasons.

Firstly, many younger employees have never been exposed to machinery or even hand tools. It is common now for new employees not to drive. Employees that do drive all learned some form of defensive driving, which is basically risk identification and asking “What if” followed by “What will I do if that happens?”

There are conflicting messages in industry, where employers say that safety is more important than production, but at the same time ask, “Do you have that done yet?” – which of course is the practical reality.

Training is frequently inadequate or not followed up on. According to the Ontario Ministry of Labour website, “Employees new to a job are three times more likely to be injured during the first month on the job than more experienced employees.”

And lastly, Flood pointed out our human instinct to react. Sometimes people reach out purely by reflex. How many of us have dropped a knife in the kitchen and questioned ourselves after the fact what we were thinking as we tried to catch it. Preventing this instinct from resulting in an injury on the job is one of the reasons the guarding is installed in the first place.

Farmer suggests a simple test for anyone questioning the safety of their machines. “Would you let an inquisitive child near the machine when it is running?” If the answer is no, the machine is not properly guarded. And to be truly proper, guarding must not impede efficient production.

Garrett Potter is the safety group administrator at Excellence in Manufacturing Consortium (EMC), a non-profit that helps Canadian manufacturers become more competitive. Email gpotter@emccanada.org for more information.

This article originally appeared in the January/February 2019 issue of Manufacturing AUTOMATION. Read the digital edition here.

Advertisement

- Feds give BlackBerry $40M for autonomous vehicles

- Honda to shut plant in Brexit-shaken Britain, affecting 3,500 jobs