Cutting costs and production time in large-scale CNC

July 13, 2017

By Thomson Industries

Jul. 13, 2017 – Automated production of large objects, such as auto body prototypes, boat hulls and surfboards, traditionally requires computerized numerical control (CNC) systems that can cost close to a million dollars.

But now, through an integration of advanced composite materials and high-precision motion control technology from Thomson Industries, a Silicon Valley company, the cost for CNC systems for cutting light-grade materials, such as wood, foam, concrete or aluminum, has been reduced by about 90 per cent.

Redefining CNC price/performance

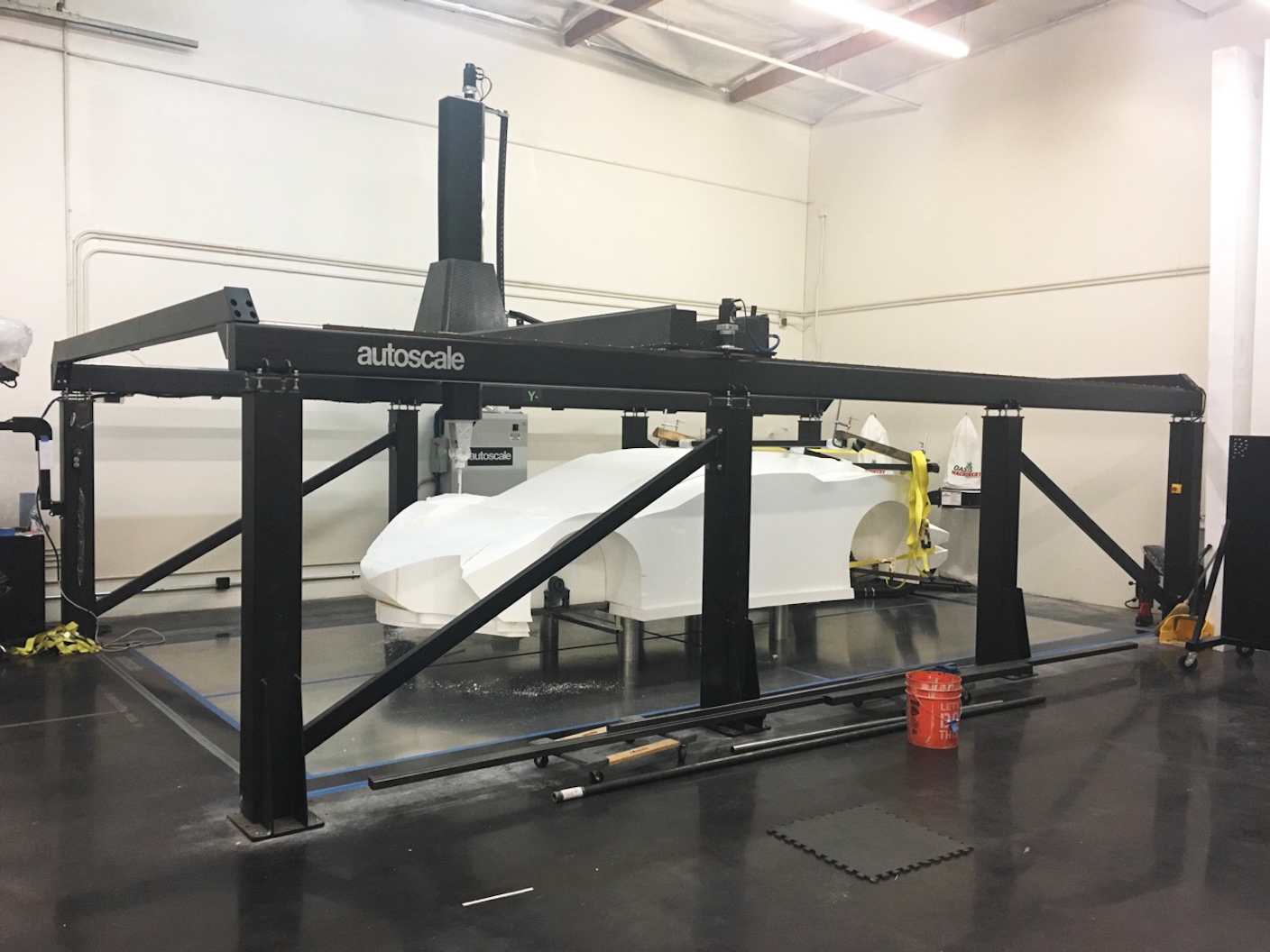

Building on experience gained through custom surfboard production, Santa Clara, Calif.-based Autoscale has developed CNC technology that can produce objects with lengths up to 16 feet. See the image below.

On the business end of a CNC system for softer materials is a router, hotwire or other cutting technology appropriate for materials, such as light woods or Expanded Polystyrene (EPS) foams. Following advanced algorithms, which product designers create for mainstream CAD/CAM software, frame components — known as gantries — guide the cutting tools along the X-Y axes, while an arm on the Z axis moves the tools vertically to add the third dimension to the product. For most mainstream systems today, the frame and all of the moving parts are composed of steel.

“When we started building larger routers, we were kind of like a dog chasing his tail,” said Autoscale founder and owner Dan Bolfing. “We wanted rigidity and speed. But adding rigidity to the moving parts also added weight, which slows the system down and adds cost. Our first models were weighing in at around 3,500 pounds, including the gantry, carriage and all the gear boxes, profile rails ball screws and other mechanisms. This is not far from what the rest of the industry was doing with steel, but we wanted to do better.”

Replacing steel with carbon fibre

After much experimentation with lighter material alternatives, Bolfing and his engineering team concluded that replacing steel with carbon fibre would offer many advantages. For one, it would be easier and faster to produce the gantries. Steel expands and contracts, and it was taking up to two weeks to get the steel gantries straight. After being welded together, they would have to be straightened and assembled. When it was determined that they were straight enough, they were pulled apart, powder coated and reassembled. Carbon fibre, on the other hand, allowed the creation of patterns and molds in advance, and when the design was laid out in the carbon fibre, it would always be faithful to the pattern, unlike steel, which twisted, turned and flexed as the temperature changed.

Most dramatic, however, was that in addition to nearly halving production time — from two weeks to about one — carbon fibre was much lighter than steel, reducing the weight of all moving parts from 3,500 pounds to 350 pounds, virtually eliminating the industry-wide rigidity/speed tradeoff, says the company. Where a steel gantry-based system might cut at 300 to 400 inches per minute, the carbon fibre-based system could cut at 800 inches per minute without vibration.

Moreover, the speed advantage comes not only in top-end speed but in ramp time as well, shortening the time it takes a system to reach its top speed, thus further reducing processing time.

“You never want to accelerate at full throttle,” said Bolfing. “With a heavy gantry, you have to ramp slowly — accelerating and decelerating at the beginning and end of every cut. The lighter the gantry, the faster you can accomplish that. With a steel gantry, you are never going to get up to 300 inches a minute on a detailed part because you are going to be constantly accelerating and decelerating. With carbon, however, you can shorten the acceleration distance by 90 per cent, which is especially valuable in finishing parts in foam, clay or soft plastics. You run faster without having drastic acceleration requirements cutting into your production time.”

Precision guidance

The key to this system’s meticulous operation, it says, is the effective use of linear guides which control the X-Y axes, and ball screws. Autoscale says it chose Thomson linear guides based on their “high precision, reliability and adaptability.”

“Thomson is the only company that provides a 16-foot profile rail,” said Bolfing. “With any other vendor, we would have to splice two shorter pieces together, which challenges accuracy and durability.”

Thomson provided complete, fully machined screw assemblies with bearing mounts ready to bolt on. For router-based operations, which tend to have a higher load, Thomson provided profile rail linear guides, noting that these would ensure smooth, precise guidance of the milling head. Thomson also supplied its Super Ball Bushing bearings, which boast 27-times the travel life of conventional linear bearings.

Besides the increase in load capacity, the Thomson Super Ball Bushing bearing is described as self-aligning, lightweight and adjustable with a low coefficient of friction.

The Thomson technology attaches to the carbon fibre-based gantries shown in the image below. Exactly how it connects, however, is highly proprietary and is a key component of Autoscale’s success, it says.

Autoscale’s new Monster CNS system with carbon fibre gantries, guided by Thomson technology.

For hotwire applications, such as those that might be used for the softest substances, Autoscale uses Thomson ball screws and round rail linear bearings to guide the hotwire cutting portion of the machine. Round rail guidance is well suited for the hotwire portion of the machine because the rail can be end-supported or intermittently supported depending on application requirements. It is less prone to jamming because of misalignment and less demanding to assemble and align than profile rail, and component costs are typically less than profile rail equivalents, says the company.

A new standard in large-scale modelling and production

For precision cutting of soft materials, including softer metals such as aluminum, Autoscale says its systems have set a new price performance standard for the cutting of large-scale products, models and prototypes. An Autoscale system costs $89,000, where a conventional system costs more than $800,000, says Autoscale, adding that its system cuts as fast as a conventional system while boasting a smaller footprint. Application areas for the new system include:

• Aerospace, including prototypes for wings, and fuselages,

• Automotive market, including race cars, smart cars, electric cars, interior consoles and exterior bodies,

• Architecture, including pre-cut concrete pool patterns, concrete staircase patterns, and concrete for pools and spas,

• Marine, including surfboards and standup boards, outrigger canoes and large boat hulls

• Furniture, including kiosks and point-of-purchase displays, and

• Custom packaging.

Future growth on the horizon

Although business is currently going quite well, Bolfing says it is looking to bigger and better things for the future. In addition to marketing his equipment, he also applies it in a separate business called Contactscale, which boasts competitive job shop services to companies that need large-scale products and prototypes. Bolfing also envisions a franchising operation in which localized job shops would purchase his system and provide local services.

The little company that started out providing custom boards to surfers is now riding a big wave.