Lean Insights: Eight tips to building a value stream map

September 20, 2010

By

Dr. Timothy

For most Lean training, I coach participants on Root Cause Analysis (RCA) through the “Asking Why Five Times” method, Ishikawa (Fishbone) diagrams and the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle. Once this training is complete, I have participants develop a current state map, detailing the processes and information flow all along the “order-to-cash” cycle.

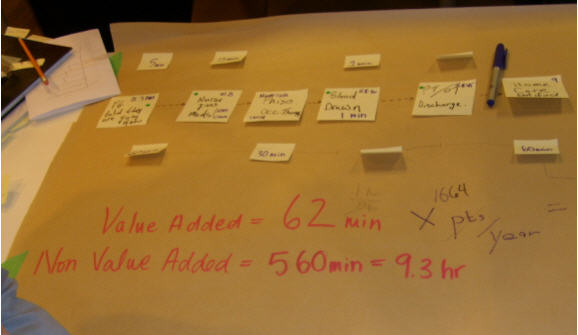

When developing a value stream map (VSM), I have participants use a large Post-it to represent a task or process, and a smaller Post-it to denote the waiting time between tasks or processes. When they are unsure about timing, I encourage them to go to the gemba – the real place, where the real problem is, and collect real data. The participants then add up all of the value-added (VA) times from the large Post-its, and the non-value-added (NVA) times from the smaller Post-its. Then, they multiply those values by the number of times that value stream is used in a year. For example, in the image below, the VA time was 62 minutes per iteration, and the NVA time was 560 minutes per iteration. Participants processed 1,664 patients a year, yielding 103,168 VA minutes and 931,840 NVA minutes, or approximately 1,720 VA hours and 15,530 NVA hours.

In this case, it was relatively easy for the participants to get accurate data because they came prepared. But what do you do when participants get stuck in the data collection process while developing a VSM? Here are some tips:

1. Identify the value stream you’re working on. Many VSM participants will try to map out a huge value stream. Help them to identify the smaller portion of the larger value stream that they’re working on.

2. Split the difference. When participants have a cycle time that varies from very large to very small, have them take an average cycle time. When you ask people to make an estimate of the average cycle time, they tend to recall the largest exception. When you remind them that they’re after the average, they tend to think of the shortest cycle time. Split the difference.

3. Go to the gemba. When participants get stuck in getting estimates for cycle times, have them go to the place where the issue is. Remember the “three reals” – the real place, the real problem and the real data.

4. Double-check the VSM. If participants are still having trouble keeping on track, have them go back to the VSM and trace the process through. If they have bitten off too much, have them put those additional processes or steps in the parking lot. It’s okay to fine-tune their VSM selection.

5. Identify the largest NVA points. This is where the surprises or “aha” moments will come. Participants will have a few large wait times between processes, and they will typically not be aware of them ahead of time.

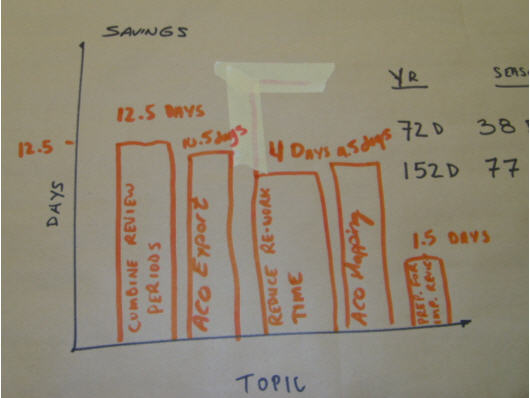

6. Rank the NVA points. Creating a Pareto chart with the NVA points ranked from largest to smallest will set the stage for which one the team will start with, and lead the way for the next deliverables.

7. Create an A3 for the first kaizen opportunity. An A3 is built on a PDCA cycle. When creating their A3, be sure to have participants include the root cause analysis section and express the projected savings in cycle-time reduction, scrap or wastage elimination. Plus, express the savings in dollar terms.

8. Add up the VA and NVA times. After adding up the VA and NVA times, multiply these totals by the number of times a year this VSM is used. This will be another “aha” moment for them. Remind them that even a little number multiplied by a big number will still result in a big number.

Remember, it’s easy for VSM participants to become overwhelmed. Follow the above points to keep people on task and diligent.

Dr. Timothy Hill is an Industrial and Organizational Psychologist and Certified Lean Six Sigma Black Belt with global expertise in Human Resources/Human Capital. He can be reached at drtim@kyoseicanada.ca.

Question from the floor

QUESTION: We’ve just finished our first Lean exercise. It was very successful, but I’m worried about keeping that enthusiasm and success. Any suggestions?

ANSWER: I hear this a lot. Often a consultant helps with the first Lean deployment and achieves some success. However, then the consultant leaves and the organization discovers that the first success was the easy part; sustaining it is the challenge.

I tell people that changing to a Lean culture takes about two years, and that Lean’s success is 20 percent Lean tools and 80 percent Lean management. Let’s look at some of the management challenges:

1. While Lean co-ordinators, facilitators and kaizen teams are invaluable, it is the role of managers and executives to create the correct environment. They need to foster the systems in which employees can and will take responsibility for the practices, behaviours and thinking that achieve, sustain and build on improvements made with Lean.

2. They need to shift the culture from the blame-based “Who” to “Why,” and introduce the critical thinking skills behind root cause analysis.

3. They need to allow employees to solve their own problems. Managers are there to facilitate and support, not to be a pair of hands.

4. Managers need to help celebrate success by helping to communicate successes – both at the end of a kaizen delivery (hansei) and outwards towards the rest of the organization (yokoten). This includes making an appearance at important Lean events, from participating in the initial training to being there for successful Lean delivery meetings.

— Dr. Timothy Hill

From the book shelf

Mike Rother, Toyota Kata: Managing People for Improvement, Adaptiveness and Superior Results

Mike Rother and John Shook wrote Learning to See, a title I’ve recommended for those who want to improve their value stream mapping. Shook also wrote Managing to Learn: Using the A3 Management Process. Both books present exceptional insight and guidance into finding kaizen opportunities and delivering on them. Toyota Kata fits right in because it addresses the rest of the human capital side of Toyota; the side missed by only addressing the Toyota Way, Liker’s 14 points or TPS/Lean.

Rother points out that “many of us are managing our companies with a logic that originated in the 1920s and 1930s; a logic that might not be appropriate to the situation in which your company finds itself today.”

He adds that Toyota accounting control systems have little or no place on factory floors. Toyota managers are taught to go to the gemba to see the three reals – the real problem, the real situation and the real data – for themselves before coming to any conclusion.

The Toyota kata that Rother refers to is the ability to be adaptive and continuously improve and maintain more focus on the details of the real situation in real time. Employees and managers bring their root cause analysis to bear. Don’t blame the people but review the processes. This emphasis on maintaining a long-term vision and responding to errors with thinking separates Toyota from that older management thinking still adhered to by many organizations.

This is a very good read, and an introduction to the rest of TPS not covered by earlier books.

Advertisement

- Cyber defence: A layered strategy to secure your control systems

- Black swans and baggage: How to manage unscheduled events