Manufacturing geometries

January 29, 2018

By Jon Robinson

3D printing begins to move past consumer hype into industrial design and onto the production floor

Ricoh’s 3D printed jigs and fixtures boost assembly line productivity

Ricoh’s 3D printed jigs and fixtures boost assembly line productivity Jan. 29, 2018 – ING in late-2017 reported the current trajectory of 3D printing could result in one-quarter of world trade being wiped out by 2060. This was its Scenario I, in which 3D printing continues to evolve at an annual growth rate of 19 per cent, with the possibility of locally 3D printed goods cutting trade by 40 per cent. Scenario II considers an accelerated 3D printing growth rate of 33 per cent, which would wipe out two-fifths of world trade by 2040. ING’s analysis also predicts, that at current growth rates, half of all manufactured goods will be printed in 40 years.

These long-term predications cannot consider all future supply-and-demand variables, of course, but today 3D printing constitutes less than 1 per cent of global manufacturing revenue. Wohlers Associates, a consultancy specializing in 3D printing research, estimates 3D printing will eventually capture 5 per cent of global manufacturing capacity, which would make it a $640 billion industry (all figures in U.S. dollars). A 2016 report called 3D Printing: The Next Revolution in Industrial Manufacturing, published by logistics giant United Parcel Service (UPS), estimates today’s 3D printing market to be worth anywhere from $7 billion to $9 billion. Consultancy firm McKinsey & Company estimates the 3D printing market could reach anywhere from $180 to $450 billion by 2025.

The range of these growth predictions largely comes from the inability to fully understand how massive companies — with the ability to shift markets — might alter manufacturing models to leverage 3D printing. It is unlikely 3D printing can predominately replace — or even penetrate — mass production processes in several sectors, but it does hold the potential to touch most any category of discrete manufacturing. IT research firm Gartner estimates 10 per cent of all discrete manufacturers will be using 3D printers by 2019 to make parts.

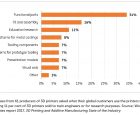

Watching 3D grow

3D printing is best suited for making complex, small-batch products, as illustrated by its heavy usage for prototypes and parts. The 2016 UPS report describes parts production as its fastest-growing application, specifically functional parts at 29 per cent and prototypes at 18 per cent. In November 2016, UPS invested in a company called Fast Radius to launch a new global logistics model for parts production via 3D printing. Fast Radius’ primary production facility is now located in what it describes as the world’s largest packaging facility, UPS WorldPort (Louisville, Ky.), which also serves as the company’s global air hub. Fast Radius explains this “strategic end-of-runway location” provides up to six hours of additional production time versus using a near-site location, typically controlled by a third-party. 3D printing will likely experience growth under a service-bureau model as technologies mature in both function and cost.

2017 research by Gartner shows interest in establishing in-house 3D printing capabilities is “rapidly gaining traction.” Gartner predicts 40 per cent of manufacturing enterprises will establish what it calls 3D printing Centers of Excellence (COE) by 2021, pointing to existing industrial-scale efforts by Boeing, Johnson & Johnson, Rolls-Royce and Siemens. In September 2016, Fortune.com reported 3D-print startup Carbon received $81 million from a group of investors, including GE Ventures, BMW Group, Nikon and JSR, as an extension of a $100-million funding round in August 2015 led by GV (formerly Google Ventures).

In December 2017, Yahoo Finance reported Carbon closed on $143 million of a new funding round. “Once completed, this round will bring the Silicon Valley-based company’s total raise to a whopping $422 million and reportedly boosts its valuation to a mighty $1.7 billion,” wrote Beth McKenna. “To provide some context, the two largest publicly traded pure-play 3D printing companies, Stratasys and 3D Systems, have market caps of $1.14 billion and $1.13 billion, respectively.”

Prospects for 3D printing growth are buoyed by venture-capital investments with established companies like UPS, which holds the world’s largest network of distribution centres. Billed as The Global Platform for Part Production, Fast Radius supports its 3D printing capabilities with third-party providers of techniques like CNC machining and injection molding.

Making 3D fit

3D printing can reduce the use of expensive processes to create tools, molds and modifications for production lines. In 2017, industrial imaging giant Ricoh began replacing some of its traditional metal tooling with lightweight 3D printed jigs and fixtures for an assembly line in Japan, where an operator typically handles more than 200 parts a day. Ricoh is assembling an electronic component using a 3D printed fixture produced in anti-static ABS plastic on a Stratasys Fortus 900mc printer.

“Because we are producing an enormous number of parts, it takes a lot of time and effort to identify the right jigs and fixtures for each one. This manual process has become even lengthier as the number of components grows, requiring that an operator examine the shape, orientation and angle of each part before taking out a tool and placing it back in its original fixture,” explained Taizo Sakaki, senior manager of business development, Ricoh Group. Ricoh would typically outsource machine cut tools that could take two weeks or more to produce, but its engineers can now determine the shape and geometry of a fixture through 3D CAD software and 3D print it in one day.

“Prototyping is the reason 3D printing exists, because there is nothing better to make one-offs particularly if it is a small part with high detail,” said Stephen Nigro, VP, inkjet and graphic solutions for HP Inc., which began launching its Multi Jet Fusion products in 2016 to disrupt the 3D printing market with a high-speed, relatively low-cost platform. HP explains on a current high-cost, high-quality laser sintering machine, for example, 1,000 gears would take at least 38 hours to fabricate, while those same 1,000 gears could be produced within three hours on Multi Jet Fusion technology.

UPS shared a telling quote in its 2016 report from an undisclosed senior industrial designer at a consumer electronics company: “Our prototype turnaround time reduced from three to six months to two to three weeks. Time-to-market for new products reduced by 40 to 60 per cent. 3D printing is viewed as an enabler here for expanding into new markets.” UPS explains the next big 3D printing opportunity is in smartphones, which comprise an estimated 35 per cent of total consumer electronics sales.

As early adopters, the consumer electronics and automotive industries each contribute 20 per cent of the total 3D printing revenue, according to UPS, with aerospace following closely behind. Mercedes-Benz Truck in 2017 began its first 3D-printed spare parts service, allowing customers to 3D print more than 30 different spare parts for cargo trucks. Logistics giant DHL, in its own November 2016 3D printing report, explains hundreds of millions of spare parts are kept in storage. DHL used data from Kazzata — an online marketplace for 3D printed spare parts — to estimate the share of excess inventories can exceed 20 per cent.

“[3D printing] may never be as efficient as a three-story stamping press at banging out ribbons of metal into panels, but, in one shot, 3D printers can form complex — indeed impossible-to-make — parts that a press could never solve,” wrote Pete Basiliere, Research VP at Gartner, which first used its highly regarded Hype Cycle Report to analyze 3D Printing in 2016 (Figure 1). “Our Predicts research highlights three industries — medical devices, aircraft and consumer goods — that are making significant strides in implementing advanced manufacturing practices enabled by 3D printing.”

Gartner research predicts 75 per cent of new commercial and military aircraft will fly with 3D-printed engine, airframe and other components by 2021. “After 20 years of use,” Basiliere explained, “Boeing has additive manufacturing at 20 sites in four countries and more than 50,000 3D-printed parts are flying on both commercial and defence programs.” He pointed to how GE Aviation’s new Advanced Turboprop engine design converted 855 conventionally manufactured parts into 12 3D-printed parts, resulting in 10 per cent more horsepower, 20 per cent fuel savings, a shorter development cycle and lower design costs. Airbus is utilizing 3D printing to introduce more than 1,000 3D-printed parts in the construction of its A350 airplanes. Basiliere also noted Airbus in 2016 unveiled a completely 3D-printed drone called Thor consisting of 50 3D-printed parts and two electric motors. “This aircraft, which is four metres long and weighs 21 kilograms, was constructed in just four weeks.”

This article was originally published in the January/February 2018 issue of Manufacturing AUTOMATION.

Advertisement

- Humber College, Festo Didactic launch five-year workforce development training program

- Sensing-Saf-Start helps protect from accidental restarts after power interruptions